What is the DNS and why does it matter?

Perhaps the best way to describe the Domain Name System, or DNS, is like a central directory or “contacts list” for the internet. The DNS is a foundational system that is critical for keeping us connected, as well as enabling a seamless exchange of information, services and more.

What exactly does the DNS do?

Humans tend to communicate with words, rather than the complicated sequences of numbers and decimal points that computers prefer.

Therefore, what the DNS does is act as a “bridge” between human and machine, translating an easily understandable web address – such as www.example.eu – into a computer-friendly, numerical IP (internet protocol) address, like: 2001:db8:3333:4444:CCCC:DDDD:EEEE:FFFF.

When you type a web address into your web browser, that address is seamlessly matched with its corresponding IP address within milliseconds, and the content you are seeking is displayed.

Likewise, the DNS also helps ensure every email you send reaches its intended destination. The DNS translates the domain name used for your email address (like gmail.com) into an IP addresses, and then directs your message to the appropriate mail server.

The DNS connects everything – and everyone

The DNS’ reach goes well beyond your web browser or email account.

Every connected device – be it a laptop, smartphone, gaming console or voice-activated home assistant – uses an IP address to communicate with and identify other devices over the internet.

Want to learn more? Watch this two-minute video for a deeper dive into the DNS and how it works:

Does anyone "run" the DNS?

Rather than one centralised organisation, there are several important groups who are involved globally in the DNS’ day to day operation. These include:

- Registries are the organisations that run top-level domains (TLDs). A TLD can be defined as the right-most label of a domain name (www.example.eu) and come in a few different forms.

Country code top-level domains (ccTLDs), which – as the name implies – correspond to specific countries, geographies and sovereign states. Examples of ccTLDs include .it for Italy, .si for Slovenia and .eu for the European Union.

Registries can also represent “generic” top-level domains that aren’t attached to any specific country or geography, like .com, .net. and .org. - Registrars: Where registry organisations administer, maintain and run top-level domains, registrars are in the business of selling domain names. Registrars will often provide additional services, including hosting and website building tools.

- ICANN, or the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, is responsible for coordinating the global policies for the DNS. Whilst the policies developed at ICANN mainly affect gTLDs (see our article on the difference between ccTLDs and gTLDs here), some of the more technical policies can have an impact on ccTLDs as well. They also manage parts of the overall internet infrastructure globally.

How does a DNS query work?

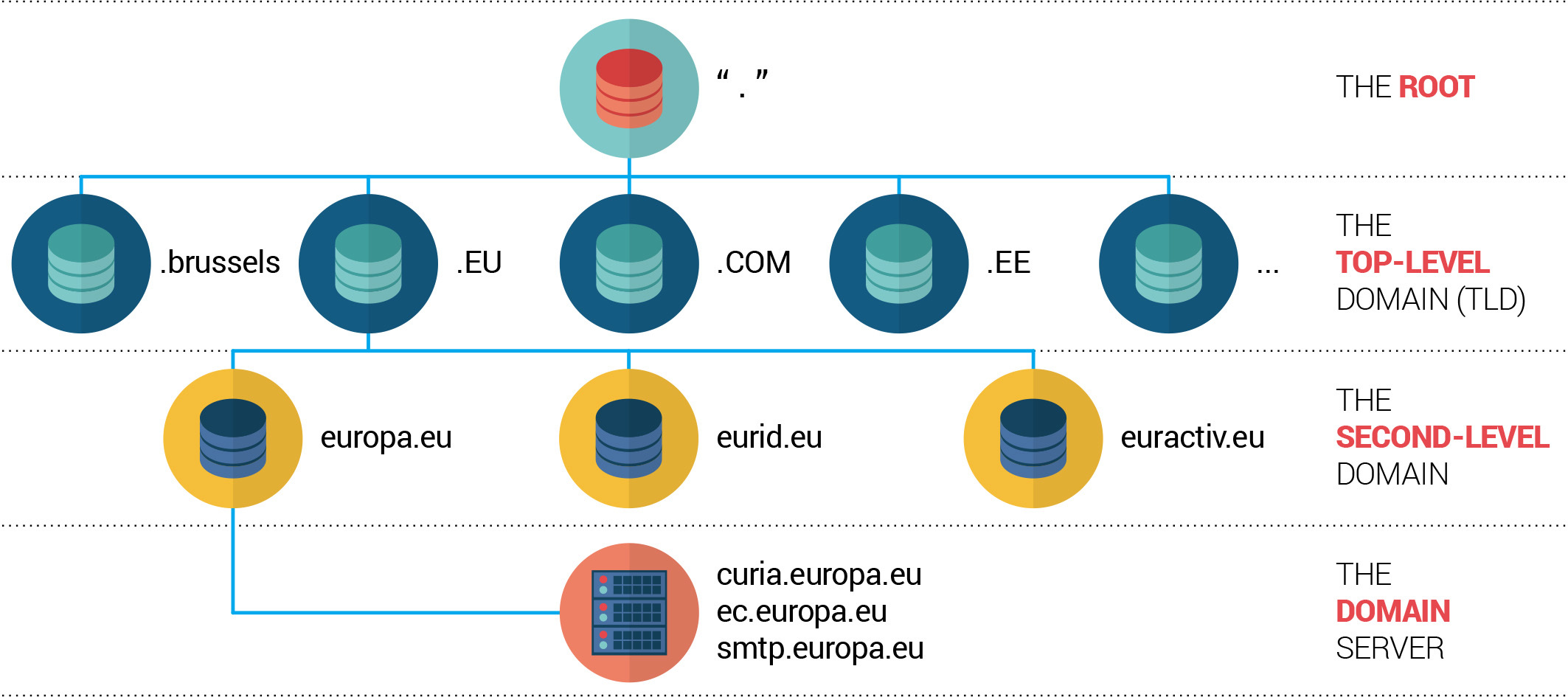

The DNS is set up as a hierarchical system, with different layers of servers (as well as organisations) exerting control and influence over the flow of information each time a query is made.

Let’s look at how this process typically unfolds:

When you type a domain name – www.example.eu, for example – into a browser, your computer starts by asking a DNS resolver (typically run by your internet service provider) for the domain name’s unique IP address.

The resolver starts by asking “at the top”, i.e., the root nameserver for the IP address of the DNS (registry) server (to find the TLD .eu). The root nameserver responds by pulling the top-level domain (TLD) – .eu – out of the query and then directing the resolver to the relevant TLD nameserver.

The .eu TLD nameserver contains (and maintains) information on all the domain names that carry the .eu extension. It is here that the unique IP address for www.example.eu is provided to the resolver.

Then – in the span of milliseconds – web pages and their content are downloaded and displayed on your computer.

In most cases, a query does not have to go all the way to the root nameservers. Your computer can retrieve the response it is seeking from a nearby “caching server” which may already have the IP address information readily available.

Where does the DNS fit within the wider internet ecosystem?

The DNS is part of the internet’s “technical layer.”

Essentially, packets (smaller segments of data sent over computer networks) travel between connected devices using infrastructure built by internet service providers and governed by protocols agreed upon by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and the Internet Architecture Bureau (IAB).

Each packet receives an IP address managed by their Regional Internet Registry (RIR). The DNS layer, then, acts as a “central directory” for these IP addresses.

The image below shows the layered structure of the internet, as well as where the internet’s governing bodies and the DNS’ main actors fit.